Pickpocket

Disparity and Despair (Part 2 of 4: An Intro to Transcendental Style in Film)

The style of this film is not that of a thriller. Using image and sound, the filmmaker strives to express the nightmare of a young man whose weaknesses lead him to commit acts of theft for which nothing destined him. However, this adventure, and the strange paths it takes, brings together two souls that may otherwise never have met.

This opening scroll that precedes even the film's title cards gives us a precise introduction to Pickpocket (1959). (“For which nothing destined him” seems to be a poor translation from onscreen French. The actual implication is that he wasn’t ‘cut out’ for this line of work.) It’s interesting that the first sentence of the introduction to a film is to say what it is not. “This film is not…a thriller.” It leaves no doubt that Bresson’s style was an objection, a deliberate rebuttal of the norms of the age in which it was released.

From Schrader’s Transcendental Style in Film:

Like Ozu, Bresson has an antipathy toward plot: “I try more and more in my films to suppress what people call plot. Plot is a novelists’s trick.” The plot “screen” establishes a simple, facile relationship between the viewer and the event: when a spectator empathizes with an action (the hero is in danger), he can later feel smug in its resolution (the hero is saved). The viewer feels that he himself has a direct contract with the workings of life, and that it is in some manner under his control. The viewer may not know how the plot will turn out (whether the hero will be saved or not), but he knows that whatever happens the plot resolution will be a direct reaction to his feelings.

Pickpocket opens with Michel (Martin LaSalle) at the horse track stealing large bills from a woman’s purse. He is caught by the police and questioned but let go for lack of evidence. He goes home and sleeps. The next day he goes to visit his mother but stops short, instead giving the neighbor, Jeanne (Marika Green), money to give to his mother. Michel meets a friend at a cafe, looking for work when a third familiar face approaches them. A conversation ensues regarding the nature of the world, and it is here we are struck by the big ideas that seem sneaked into a film we thought was about thievery. The expected style (thriller) is punctured by the thought that even these people, entirely driven by the forces the world exerts on them, are aware of the more significant nature of all things.

The close-up camera work that Bresson is known for is ideally suited to a film where the characters require proximity and closeness. The movie can feel claustrophobic, giving us the necessary perspective to understand Michel’s experience. Wallets, bills, newspapers, the fabric of clothing; we see it in closer detail than we’re used to seeing in any film, past or present. Further, the sound design of the film pulls us into the scenery. Attention to detail is vital: the floorboards in the old apartment creak and the footsteps clack on the station platform when passengers bustle out towards the exits. Traffic buzzes in the background. This attention to detail gives us long periods in which the tension and weight of Michel’s actions can be felt. I wished he would abandon his ventures in crime and find another way to “escape.” We don’t ever understand what it is that Michel is trying to escape, but we don’t need to. Destitution, repression, depression, ennui; it’s easy for us to project our own experience onto the gray canvas of Michel.

In Schrader's estimation, disparity is one of the formal elements at play that is required for transcendental style. In the context of film, and put simply, disparity describes our expectations as viewers versus what is happening on the screen. As viewers, we watch a film expecting an outcome based on what we know: for Tarantino, we might expect a subversion of historical reality. For Hamaguchi, we might expect many hours of character driven stoic realism with a cathartic understated finale. For any typical modern film you might watch, you’ve probably experienced the boredom of knowing what would happen next. (Romantic comedies come to mind.) Disparity occurs when our expectations are indeed not met. When we experience a scene in the same way we would experience personal tragedy or elation. Our eyes are telling us what we refuse to believe. We believe what is happening while not believing what is happening.

From Schrader:

The viewer finds himself in a dilemma: the environment suggests documentary realism, yet the central character suggests spiritual passion. This dilemma produces an emotional strain: the viewer wants to empathize…yet the everyday structure warns him that his feelings will be of no avail…This “strange air” is the product of disparity: spiritual density within a factual world creates a sense of emotional weight within an unfeeling environment.

A rough example: If we see a car crash and a death of a character in a film, and the scene that follows is the family of the victim in anguish, distraught, wailing, etc., we understand and accept the events and allow the film to continue to guide us along whatever arc it’s putting forward. If we see that same car crash and death, but what follows is various family members continuing with their lives in ways we don’t expect to see: a daughter doing taxes and staring out the window, an uncle getting dressed for work; we are forced to infer what these characters are experiencing. The disparity (our expectations versus what is happening) pushes us to find our own emotional connection to the work. The rebuttal of the style of the age (“thrillers,” according to the opening) is critical to the film’s transcendental style.

A sense of danger creeps into the frame when Michel follows a strange man out of his apartment and to a bar. But is danger present? Your understanding of the world and the films that inhabit it will be the most significant factor in how you interpret this sequence: Michel follows the man to a bar. The man takes him to a backroom, where-in we are presented with a montage of close-ups: hands doing things, practicing specific movements, being near other hands. The voice-over tells us: “There in that small bar, I learned most of my tricks.” A hand flicks a button open on a suit jacket. “He taught me generously and freely.” Another hand removes a pen from one man’s pocket and slides it into another’s sleeve. Without any obvious hint from the film, I saw a psychosexual meaning to these scenes that could be overlooked by another viewer. In terms of transcendental style, an audience of the era might have felt spoken to in a way they’d never felt from a “modern film.” A different audience might assign the feeling of danger to something else entirely.

The film forces the viewer to bridge the disparity in order to find meaning. The film keeps our interest in the loosest of grips, allowing our minds to probe. That loose grip, or soft touch, makes Bresson’s films arresting. We are interested and intrigued by what’s going on, but the course of events does not sensationalize us. A scene isn’t setting up the next, which is setting up the next until we eventually arrive at a satisfying conclusion. The over-arching plot isn’t as crucial as the unpredictability of the journey.

Pickpocket is a stunning 75-minute watch that you could return to repeatedly and find new vectors of interpretation. It is a movie about fleeing despair in an attempt to approach and defeat it. To solve problems by avoiding them. To win the race by not entering. The film ends suddenly, logically, and cuts to black. The orchestral soundtrack rises and continues to play while we’re left sitting in the darkness. Alone with our thoughts.

Pickpocket

Written and Directed by Robert Bresson

1959

75 minutes

French

Stray Thoughts from the Editor

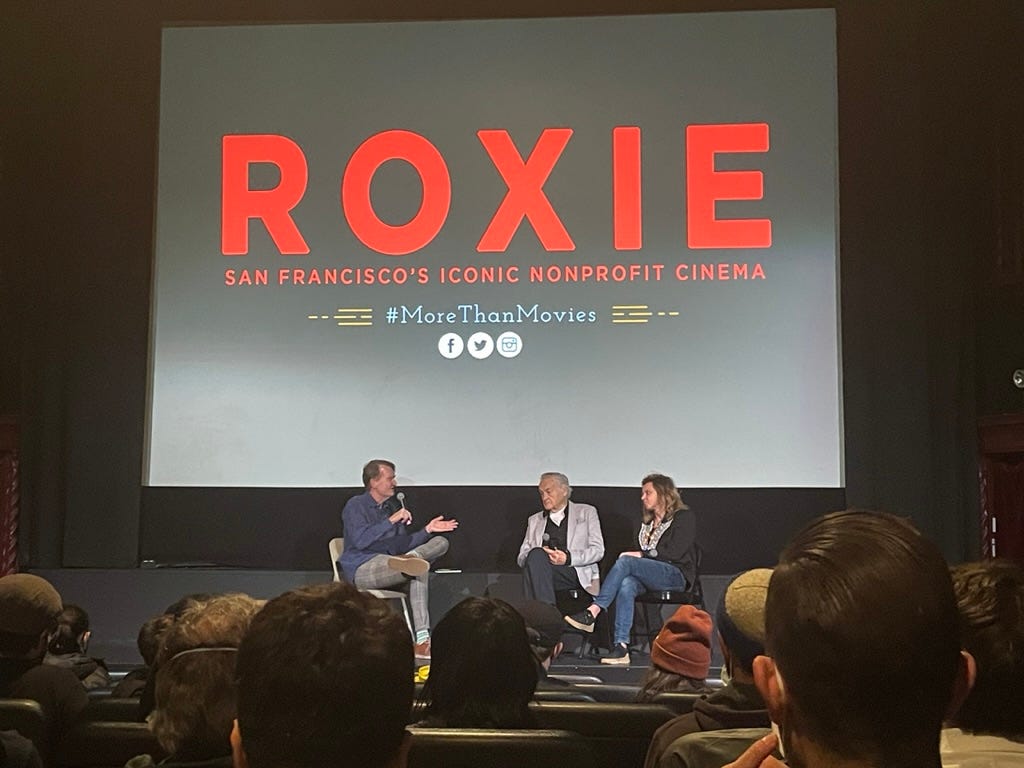

May (my fiancée) and I recently had the pleasure of seeing EO at San Francisco’s hallowed Roxie theater in the Mission. Jerzy Skolimowski, the director of the film, and Ewa Piaskowska, one of the producers of the film, were also in attendance and did a brief Q&A at the end of the showing.

This is a remarkable movie that embodies transcendental style and is worth seeking out. It has a strong connection to this week’s movie in that Robert Bresson’s film Au Hasard Balthazar is the spiritual predecessor of EO. Manohla Dargis, the co-chief film critic of the New York Times, named EO as her top film of 2022 and wrote an excellent review that is worth checking out as well; it’s a great piece of criticism. EO is a stirring indictment of the relationship between humans and animals. At the end of the Q&A, Skolimowski made an appeal, in his slow and introspective drawl, for all of us to take better care of animals and reduce our meat consumption if possible. As he said: "We need to take care of our little brothers."

It's interesting that Bresson says that plot is a novelist's trick, since I think French writers of the same period were also rejecting this idea of plot. Really wonderful summary.