Schindler's List

What is the value of human life?

We begin in full color with a prayer in Hebrew, in observance of Shabbat, before the candles go out and the world becomes black and white.

Schindler’s List (1993) is best viewed as an ensemble film. The singular story of Oskar Schindler, a man who sacrificed personal comfort and fortune in order to save hundreds of lives, is told in a straightforward narrative, with fine performances from Liam Neeson and Ben Kingsley. But the more important story, the one worthy of our time and focus, the one that seems to be fading from public memory, is the plight of the Jewish people.

Suppose you can put aside the reputation of this film going into it and how that reputation will likely inform your expectations of how difficult this watch will be. In that case, the movie does an exceptional job of starting us in a place of muted terror; We’re insulated from the true horror of war (not unlike today) and only sort of feel the slow-turning screws; until our thumbnails split. Suddenly we’ve crossed an event horizon. We see Jewish people get forced onto cattle cars. A long take of their luggage (neatly labeled, in a tragic stroke, indicating the faint hope that they might one day be reunited with it) being carted into a warehouse for unloading, sorting, and caching. Once the atrocity begins, it only lets up when we’re with Oskar Schindler as he, in Hollywood fashion, cleverly schemes to do good. It’s impossible to mentally prepare for watching Schindler’s List. (Especially if you’re a first-time viewer.) You might think you’re only getting the story of Oskar Schindler, but Spielberg acutely understands that histories only work with context, and more than any other film he’s made, he gives this one a lot of space for just that. It’s difficult to watch but essential.

The famous sequence of the anonymous girl in the red dress (pictured above) plays as if we’re reading a diary; a summary of a horrible event that takes a detour and gets lost on a detail; a type of shoe, an impenetrable expression on a face, a crack in some marble. It breaks away from time and haunts us from a parallel vector. It’s interesting to watch Schindler’s List at a remove from its release and imagine it in the pantheon of great films from the last hundred years. What will change when Liam Neeson is less well remembered, when an entirely new age of actors/entertainers is upon film viewers, and Oskar Schindler is made to stand on his own? Will he still be a hero?

Liam Neeson puts on an outstanding and more concise performance here than in any movie I’ve seen him in. He plays Schindler like a fiddle. Schindler understands better than anyone around him what motivates many (not all) Nazis: money and survival. They were people going along with an ideology of hate out of selfish convenience. They were people that saw a chance to improve their station in life. It should provoke thought about what motivates much hate today. When wrestling children away from soldiers at Auschwitz, Schindler makes no appeals to humanity. He angrily explains to the Nazi soldiers that the children’s hands are better for polishing the insides of shell casings at his factory. The Nazis relent only when presented with this viewpoint.

Ralph Fiennes operates with such sniveling coldness that it’s clear why casting him as Voldemort, a more straightforward representation of evil, was a layup. (Voldemort doesn’t hold a candle to Amon Goethe.) Goethe is an emotional child with a gun and soldiers. He is incapable of valuing human life. Late in the film, Schindler asks him several times in earnest, “What’s a person worth to you?” Goethe proves incapable of answering. He can’t understand why Schindler would pay valuable money for Jewish prisoners. “No, what’s a person worth to you?” he begs Schindler. Here we see a man who can’t value something unless he understands how someone else appreciates it, as a child would deduce value from the adults around them.

So what is there to say about Schindler’s List? In terms of a film’s message and craft, it sits at the top of the bell curve: “Whoever saves one life saves the world entire.” I can offer a critique from today’s vantage point: Oskar Schindler is a man with power and privilege who happens to be good. He is not entirely benevolent, his journey begins in an effort to profit from war after all, but he is principled. Too many modern films glorify these types of characters, a la The Blind Side (2009). For an audience that may lack Schindler’s privilege and means, what are we to take from this? I fear that in the present, we lack role models more akin to working-class heroes than upper-class saviors. Schindler is the least brave person (villains excepted) in this film, yet he is the eponymous character. I do not doubt that the real Oskar Schindler performed good in his life, the evidence of which appears on the screen throughout the film. I question the wisdom of making him the magically benevolent hero of this story. In reality, the Holocaust is a story without heroes. In one scene, he pulls a worker off the line and asks him why he isn’t celebrating the Sabbath, as if this person should’ve felt free to do so under the circumstances. He is like a reformed Ebenezer Scrooge berating a gaslit Bob Cratchit for coming to work on Christmas.

Claude Lanzmann, director of the landmark film Shoah (1985) (read more about it here), wrote an op-ed on Schindler’s List for the Dutch newspaper NRC Handelsblad in 1994. Lanzmann writes:

Humble and proud I sincerely thought that there was a time before Shoah, and a time after Shoah, and that after Shoah certain things could no longer be done. Spielberg did them anyway.

The thing I reproach Spielberg is, that he shows the holocaust through the eyes of a German. Even though it was a German who saved jews, yet this completely changes the perspective on History. It is the world in reverse. Shoah disallows many things for people, Shoah is a lean and pure film. In Shoah there is not a single personal story. The jewish survivors in Shoah are not merely survivors, but people who were at the end of a chain of extermination, and who witnessed directly how their people were murdered. Shoah is a film about the dead and not at all about survival.

Viewing the film today, we’re presented with two polar extremes: The heroic Oskar Schindler, defending the Jewish people like a superman, and the villainous Nazis. As audience members, we’re inclined to identify with the hero, which allows us to leave the theater satisfied that justice is done.

To be fair, Spielberg spends half of the film ensuring that we see the context for this story: the horror at the periphery, but he spares us the stark finality that most Jewish people experienced in the Holocaust.

This criticism aside, Schindler’s List remains a must-watch. Make time for it in your life. It is a film made by a master at the height of his powers. It is an accessible entry into history and asks a question that must be highlighted, never lost sight of, and repeatedly answered by future generations: what is the value of human life?

Schindler’s List

Written by Thomas Keneally and Steven Zaillian; Directed by Steven Spielberg

1993

195 minutes

English, Hebrew

Not so Stray Thoughts from the Editor

Back in November, I recommended Munich to Dae since he’d mentioned he hadn’t seen it, and he told me he’d only watch it if I finally watched Schindler’s List, which I hadn’t seen. Here we are.

And that’s a wrap for 2022! What a fantastic year for film-going! We even covered a few 2022 releases here on Movie Night. I’ve yet to see everything on my list for 2022 (Aftersun, Fabelmans, EO, among others), but I’ve compiled a list of my favorites on Letterboxd here.

I write this final post of the year on a rainy San Francisco afternoon from a location that was featured heavily in a notable 2021 release:

Recognize it?

In other news, I’m happy to report that Movie Night has joined Letterboxd as an HQ member. Future lists can be found over there, along with everything Movie Night recommended this year.

2022 was the first year for Movie Night, so we weren’t able to recommend a movie for every week, but I’m proud that we have been able to post every week since launch. In that time we:

Recommended 45 films

Wrote 41,062 words about movies.

Spanned 10 “genres” (these can be hard to define, but if you guessed “Drama” was the number 1 genre, you guessed right!)

Had three excellent guest writers: Thank you, Dae, Amani, and Oli!

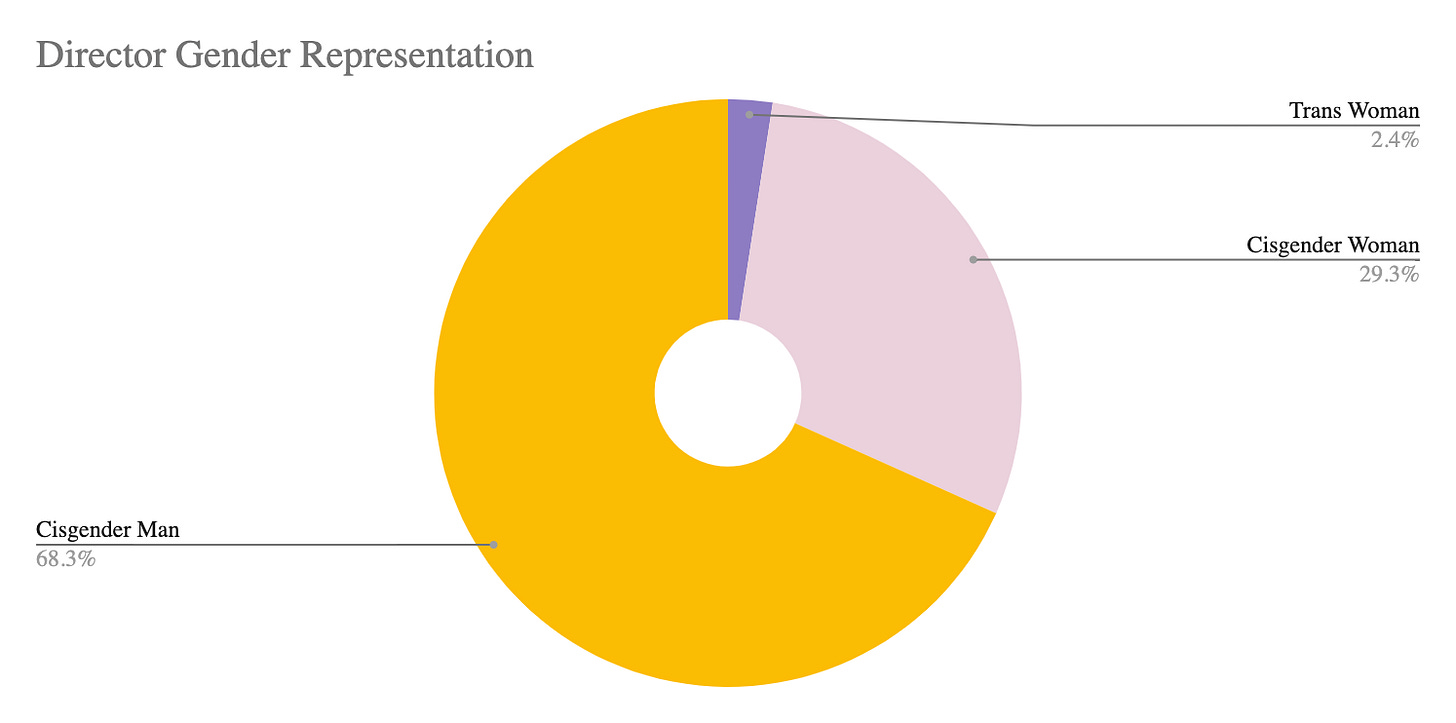

I’d also like to share some data I’ve been collecting in the background, as a way to better understand our viewing habits and ‘movie diet,’ but also to better ensure diversity in recommendations:

And for fun, here’s the breakdown of films recommended by the year they were released:

I’m no data scientist, but I can spot a trend when I see one. Next year we’ll revisit these charts and see if we can’t do any better in recommending diverse and compelling work from around the world.

Thank you for reading along in 2022. I wish you a happy and fortune-filled 2023 with many wonderful viewing experiences!

You're a really good writer, Jeff. The ONLY thing I don't agree with is that the Holocaust is a story without heroes. It's definitely a story with not enough heroes. But there were some right???